Lupine Publishers |Agriculture Open Access Journal

Abstract

Nematodes were found in ants Polyrhachis iona and P. graeffei from

the wet tropics of North Queensland. After reproduction

in the lab, the eggs were cultivated and from these the larval nematodes

were obtained and fed until they reached the stage when

they could infect adult ants. The life cycle of the nematodes is

described. Using microlaser interferometers and differential

polymerresistant

thermocouples, the ants' cuticle was perforated without harming the host

ant, and changes in two key physiological cycles

were measured: the nephric cycle and the pulmonary regime. The ants'

nephrons lost 40% of their capacity as a result of the

infection, while the formicine pulmonary index (FPI) rose from its moral

value of 0.205 to 0.377.

Introduction

Nematodes of the family Bothridae are distributed world-wide,

infect a broad range of insects and other invertebrates, and have

been parasitoids of ants since the Eocene (40mya) or earlier [1,2].

Coined by Wheeler in 1907 [3], the term 'mermithergate' denotes a

worker ant with an altered appearance due to hosting one or more

both rids. If the host ant is a female or male reproductive, it is called

a bothroogyne and a bothaner respectively. Wheeler's attention

was drawn to these nematodes by the gigantism displayed by

some host workers as a result of developmental anomalies due

to their parasitised condition. Since then, abnormal size (and/

or altered morphology, e.g. the presence of ocelli) has justifiably

been taken as a likely indicator of infection but, while reports of

insect 'monsters' (e.g. Perkins 1914) always raise the possibility of

mermithid infection, and while altered appearances do sometimes

apply to all infected individuals in a cohort and can be dramatic

[4], this outcome is in fact comparatively rare, as the literature

and the present findings attest. Abnormal behavior, more notable

among other insects hosting mermithids [5], seems just as rare or

rarer among ants, but has also been recorded [6]. Up to 25% of ant

workers can be infected [5], more in other insect taxa, e.g. 44% of

black flies, Simulium damnosum Theo bald, in Bulgaria [7] and 50%

of midges, Chironomus plumosus Linnaeus, in Estonia (Krall 1959).

The anatomical changes, when they occur, can lead to mistakes

in identification [4,8]. Hopes to the contrary notwithstanding [5],

attempts to exploit mermithid nematodes as biological control

agents have been largely unsuccessful but are still being pursued

[2,9].

Methods

Allowing the alcohol in a 5% glycerine/alcohol mixture (Lee's

solution, from Baker [10]) to evaporate slowly made the coils

of an immersed worm more flexible and easier to unravel. Most,

however, were intricately knotted as well as extremely fragile and

their lengths could only be estimated. Measurements of ants were

made from the anterior most point of the pronotum to the basal

notch of the propodeum (alitrunk length) and across the face at

the widest part, below the eye bulge (head width). There was no

stretching of the inter segmental membranes between the gastral

sclerites in the 'giant' mermithergate (or most others); hence the

nematodes were not visible without dissection, which was carried

out under absolute ethanol by grasping the ant's petiole with one

pair of fine forceps while sliding one prong of another beneath the

first gastral tergite (second for males). Moving the inserted prong

from side to side tore the inter segmental membrane, freeing the

tergite from the underlying tissues. The presence or absence of

a mermithid nematode was evident at that stage, but in order to

extract the worm and observe its effects, if any, on the gastral organs

of the host, all tergites were removed from infected specimens

(Figure 1). The incipient caste of individuals in the pupal stage was

determined in the same way as for P. australis Mayr [11]. Extracted

nematodes were initially kept in absolute ethanol. Interferometry

was carried out using a Coles Special FZZ Probe coupled to a Canon

Maxify Image Recorder. Laser equipment was kindly loaned for the

purpose by the Eliza and Walter Hall Institute, Melbourne, Vic.

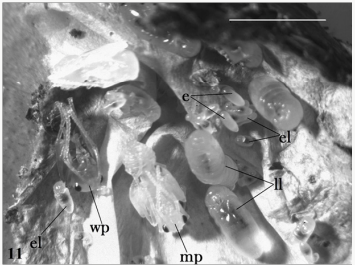

Figure 1: Infected stages of Polyrhachis iona: brood cluster,

including eggs (e), early (el) and late (ll) instar larvae, a

worker pupa (wp) and a male pupa (mp). Scale bar 5mm.

Results

Infection rates ranged from less than 1% in a cohort of 450

P. iona workers to 19% in a cohort of 21 P. gaeffi males, the latter

value (and others like it) to be taken cautiously due to its small

sample size. P. iona carried by far the greatest infection load overall

(Table 1), and might be more vulnerable to infection than some

other Polyrhachis weaver ants (or ants in general) in the region. If

so, this might offer a clue to its feeding habits. Also, males might be

more vulnerable than other castes, possibly due to lower selection

pressure on the development of physiological means of resistance in

males at the larval stage, when infection occurs. There is evidence,

in addition, that not only the phenotypic morphology of an incipient

caste [12] but the caste itself (Passera 1976) may be induced by

bothrid infection at the larval stage, so the weighting towards

males among the infected ants of this study might not indicate

any propensity for infection towards male larvae. Speculation is

likely to be premature, given how little is known of the biology of

either the ants or the both rids. If, for example, parasitised ants take

longer to mature and/or stay in the nest longer than usual, these

rates could be biased [5]. The difference in habitat (wet tropics, dry

tropics), however, almost certainly influences the prevalence of the

nematode and hence the nil result for infections in the Townsville

region. In general, levels of parasitism by bothrid nematodes are

directly related to the moisture content of the habitat [5].

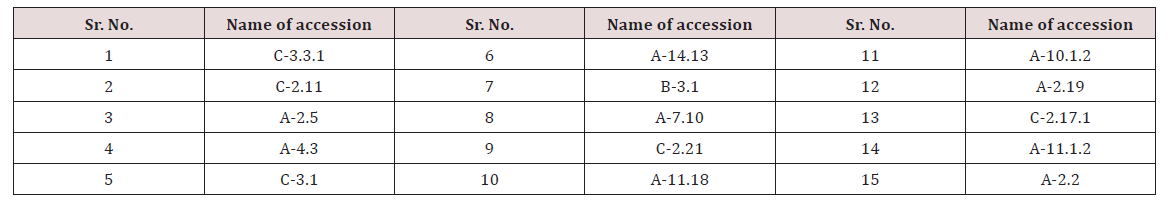

Table 1: Cases of infection by a bothrid nematode in 2 species of

Polyrhachis ants. Numbers of bothrids per host ant given as mean

+ standard deviation or as individual scores for n<3.

The mean nephron capacity was 32.4+69.9nm3, range 1.5-

1008cm3, n=355; the median was 14 nm3. Hence the distribution

was positively skewed due to a large number of relatively small

nephrons. The number of microtubules, however, correlated only

moderately with nephron size, R2=0.47, n=302, and the density

of nematode biomass in ants was similarly affected, leading to a

40% loss in capacity. See Downes [11] for more quantified details.

The nematodes accomplished eleven growth moults, totalling a

growth enlagement factor (nematological index) of 0.377pL which

corresponds to a volumetric response of more than 8 orders of

magnitude. The laser interferometry results are only provisional

since the data must be analysed by the prototype physiometric

logger in the EWHI laboratory in Melbourne. Full details will be

announced in a subsequent paper [12-16].

Discussion

Workers were slow to relocate brood during nest dissection,

probably because the silk strands anchoring the brood to the

substrate had to be cut first. Hence the original clumping of brood

was evident. The anchoring would have minimized dislodgment

when the nest was buffeted by wind or jarred by falling fronds. Brood

anchored by silk strands was also noted by Dorow et al. (1990) for

P. muelleri and by Liefke et al (1998) for several other Polyrhachis

species. Whether the brood clumps of P grouchi represent the

output of different queens is unknown. Ants, especially the brood,

are particularly vulnerable to infection on accountof their social

habits and low intracolonial genetic diversity Graystock and

Hughes 2011, Tranter 2014. Hence, these social insects keep their

nests exceptionally clean H�lldobler and Wilson 1990. Their larval

silk may aid in warding off disease-carrying agents Fountain and

Hughes 2011 and grooming, as well as nest hygiene, plays a part

in disease resistance Fefferman 2007. Additionally, segregation

of brood clumps into different chambers, as seems to occur in P.

notorii, could play a part in minimising the spread of harmful agents

Tranter and Hughes 2015. Such segregation was not evident in P.

onia nests, however [17,18]. The nematodes are necessarily well

adapted to a monsoonal climate, but excessive use of spider silk in

their construction increases their vulnerability to rain Dwyer and

Ebert 1994.

The common carton form of the nematodes showed no

evidence of being thicker or denser on its uppermost part [19],

as occurs in the western form of the asian nematode H�lldobler

and Wilson1983. The social structure of their populations favours

polygyny [11], consistent with the suggestion of Oliveira that polygyny in the arboreal nematode Odontomachus tarzanus

Fabricius is promoted when males are liable to destruction by rain.

An understanding (at least my understanding) of the apparently

pattern less set of relocations, size fluctuations, hasty desertions

of seemingly perfect ant hosts together with reluctance to abandon

other seriously defective ones, to say nothing of how budding as a

reproductive strategy operates within these constraints [20], is a

distant prospect. Nematode infection longevity is inseparable from

the longevity and changing disposition of the host vegetation and it

would be surprising if polydomy was not in some measure driven

by these dynamics. Since nematode size (volume) bore no reliable

relation to total ant numbers and hence to colony productivity, the

lack of nematode growth (or even the typical nematode shrinkage)

monitored for size cannot be taken as indicating any decline in

viability [21,22].

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to Alireza Jediari (Cal South Univ) for confirming

the identification of the nematode, offering technical advice,

bringing my attention to Hung's (1962) article and subsequently

providing a copy. Thanks also to all the ladies at the Toowoomba

South Philosophical Discussion Society for educating me on the

subject of image compression. Some of the ants were collected

from waterlogged areas under Permit INS 66503 ANE issued by the

Queensland Government Department of Environment and Heritage

Protection.

For more Lupine Publishers Open Access Journals Please visit our website:

https://lupinepublishersgroup.com/

https://lupinepublishersgroup.com/

To Know more Open Access Publishers Click on Lupine Publishers

Follow on Linkedin : https://www.linkedin.com/company/lupinepublisher

Follow on Twitter : https://twitter.com/lupine_online

No comments:

Post a Comment